In my column last week, I offered some personal thoughts about the nature of the presidential race this election season and both candidates’ removal by several light years from the experience of ordinary Americans. Each candidate has skills and deficits. Both are remote in wealth, privilege, influence and education from our nation’s everyday life as many millions of citizens actually live it.

Wealth, of course, can result in great generosity. And it needn’t disqualify a person from national leadership – but in a real democracy, belligerent egotism, political-class derision for whole blocs of the voting population, and an elitist, insider sense of entitlement to power, clearly do. All three of these behaviors are prominent in this year’s election. And American Catholics, however they end up deciding to vote, have good reason to be frustrated with the choices they face in both major parties.

Politics involves the exercise of power for good or for ill. Therefore politics always has a moral dimension. And while politics is never the primary focus of a Christian life, Christians can’t avoid applying their faith to their political reasoning without betraying their vocation as disciples. Christians should never be “of” this world, but we’re most definitely in this world. We have the privilege and duty to engage the world, including the public square, with the truth of Jesus Christ. To put it plainly: The separation of Church and state does not mean, has never meant, and can never mean, the separation of our religious faith from our political, economic and social lives.

We also need to remember one other thing: The Church belongs to Jesus Christ, not to us. The Church is his spouse and our mother, not our personal property; and if we revise or ignore her teachings according to our own opinions or vanities or convenience, we’re simply lying to ourselves and to others.

Eight years ago, “conservative” Catholics were criticized by Catholic “progressives” as culture warriors and apologists for the Bush presidency. But Catholic progressives have played the same role, often more effectively, for the Obama presidency. And if we hold the Bush years responsible for the consequences of a naïve and disastrous war in Iraq, we also need to hold the Obama years accountable for a systematic, ideologically driven attack on the unborn child, on our historic understandings of sexuality, marriage and family life, and on religious liberty.

Here’s the point: The deepest issues we face as a Church and a nation this year won’t be solved by an election. That’s not an excuse to remove ourselves from the public square. We do need to think and vote this November guided by properly formed Catholic consciences. But as believers, our task now is much more difficult and long-term. We need to recover our Catholic faith as a unifying identity across party lines. And we can only do that by genuinely placing the Church and her teachings – all her teachings, rightly ordered — first in our priorities. Larger forces shape our current realities. If we fail to understand those forces, we’ll inevitably cripple our ability to communicate Jesus Christ to generations not yet born.

I’ll close by suggesting at least one place to begin our thinking. One of the most thought-provoking commentaries I’ve seen in the last year appeared earlier this week (August 15), penned by First Things editor R.R. Reno. Readers can find it easily on the web. But with the author’s permission, I include the full text here. We don’t need to agree with it. But we’d be unwise to ignore the issues it raises.

* * * * *

THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM

By R.R. Reno

Of all our major columnists, Peggy Noonan has thought the most deeply about the anti-establishment sentiments roiling our political culture.

In last week’s [Wall Street Journal] column, “How Global Elites Forsake Their Countrymen,” she puts her finger on the central issue. Ordinary people in Germany, Great Britain, France, America, and elsewhere aren’t just experiencing the dislocations of economic globalization. They’re not simply responding to cultural change, which is often driven by immigration. They’re losing their trust in those who rule them.

As Noonan puts it, over the last generation there has been “a kind of historic decoupling between the top and the bottom in the West that did not, in more moderate recent times, exist.” Those at the top of society no longer share the interests of those less fortunate. “At its heart it is not only a detachment from, but a lack of interest in, the lives of your countrymen, of those who are not at the table, and who understand that they’ve been abandoned by their leaders’ selfishness and mad virtue-signaling.”

I’ve written about this phenomenon in the American context. It’s striking how often our leadership, both right and left, punches down. Conservatives call half of Americans “takers.” Liberals call them “bigots.” I can’t count the number of columns Bret Stephens has written in the last six months expressing his unqualified horror over the ignorance and stupidity of the Republican voters who have the temerity to reject the political wisdom of their betters.

Noonan admits she hasn’t quite gotten her mind around this decoupling of the leaders from the led. I, too, am struggling to understand. It’s odd, as Noonan says, “that our elites have abandoned or are abandoning the idea that they belong to a country, that they have ties that bring responsibilities, that they should feel loyalty to their people or, at the very least, a grounded respect.”

Viewed humanly, yes, it is odd. We have a need to belong. Loyalty is a natural human impulse. But a recent book by international economist Branko Milanovic, Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, has helped me grasp some of the underlying forces that are driving the leaders away from the led.

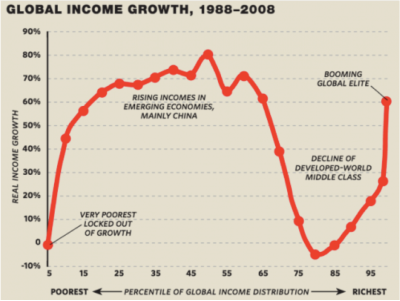

Milanovic draws attention to an “elephant graph,” so called because it looks like the hulking body of an elephant raising its trunk. On the horizontal axis, we see global income distribution. The citizens of very poor countries are at the elephant’s back end. Their median income is quite low. Those on the trunk-end of the elephant are the citizens of developed countries. The vertical axis charts the rate of growth of incomes. Here we see a very telling story. Emerging economies have given birth to a new middle class that has experienced rapid income growth. Meanwhile, the rich world is diverging. Middle-class wage growth is stagnant in the globalized economy, while the well-to-do have seen great gains.

Much of the story this graph tells is well known. We’ve heard a great deal about income inequality in recent years. But seeing the whole world at a glance shows something more. Those whom Noonan called “the protected,” which is to say the rich and powerful in the West, share with the rising middle class in the developing world a remarkable harmony of interests. Both cohorts benefit from the new global system. By contrast, in the West, the middle class is losing ground.

In short, the global system—which is committed to the free flow of labor, goods, and capital—works well for the leadership class in Europe and North America, as it does for striving workers in China, India, and elsewhere. It doesn’t work so well for the middle class in the West. Thus, in the West, the led no longer share the economic interests of their leaders.

It’s natural, therefore, to see a decoupling. We’re fallen human beings. We often develop convictions that conveniently correspond to our interests. When it comes to the rising nationalism in Europe, elites there see as much. They don’t interpret the striking new support for right-wing parties as expressions of patriotic fervor, but instead see patriotic rhetoric as a front for, at best, economic frustration, but more often racism and xenophobia.

What elites don’t see is how their own interests are dressed up as cosmopolitan idealism. Noonan points out that German elites compliment themselves on the moral rectitude of Angela Merkel’s decision to admit a million Muslim migrants. True, but they’re also insulated from the consequences. And more than insulated, they stand to benefit from lower labor costs.

Over time, the elephant graph predicts large-scale changes in democratic politics in the West. Elites now have a strong interest in weakening the nation-state, and thus diminishing the power of the voters to whom they are accountable. A radical ideology of open borders is one way to do that. Another way is to increase the power of international human rights tribunals. In a decade’s time I can easily imagine rulings that override national majorities that are deemed “unprogressive.”

But I need not evoke the future. For at least a generation, America’s most elite colleges and universities have explicitly refashioned themselves as global institutions. By implication, they are no longer accountable to America’s national interest. Their mission is more noble: the world’s interest. The same dynamic gets repeated in the corporate world. Silicon Valley answers to the world, not to America.

What goes unnoticed is the fact that a global mission provides reasons to discount the concerns of non-elites in America. Convenient theories about the inherent racism of ordinary people nicely discredit their opinions. The critical fire of a plastic, easily manipulated multi-culturalism can be trained this way or that to degrade patriotic loyalties. Meanwhile, a strict utilitarianism tells us citizenship is a construct designed to secure “rents.” Ordinary people feel abandoned and frustration builds, driving today’s populism.

Noonan is right. The decoupling of the leaders and the led is “something big.” The economic forces driving this decoupling are powerful. The ideological supports—a morally superior cosmopolitanism, a flexible multi-culturalism, and now dominant utilitarian thinking—are strong. As I’ve written elsewhere, odds are good that the democratic era will come to an end. The elephant chart suggests the future will be one of empire.

- R. Reno is editor of First Things.

# # #

Editor’s Note: Columns will be published each week on www.CatholicPhilly.com and can also be found at https://archphila.org/archbishop-chaput/statements/statements.php.

![]() Archbishop Charles J. Chaput

Archbishop Charles J. Chaput![]() Archdiocese of Philadelphia

Archdiocese of Philadelphia![]() ArchPhilly

ArchPhilly