Most Reverend Philip Tartaglia, Archbishop of Glasgow

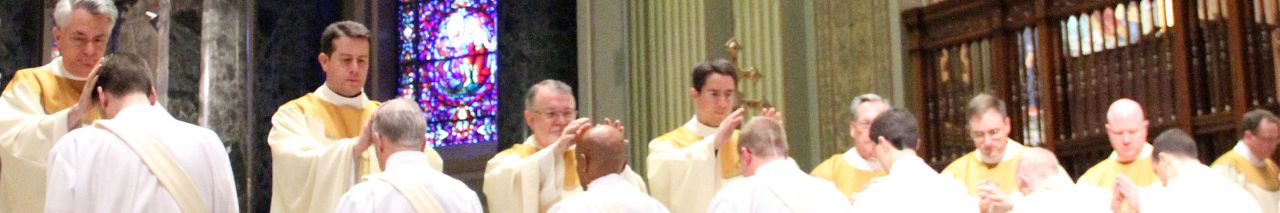

Convocation of Priests of the Arhdiocese of Philadelphia—May 2017

I want to begin this final talk with a simple fact: The Catholic Church is a bone in the throat of our secular culture. We’ve all felt its subtle — and often not so subtle – contempt for Catholic moral teaching, especially when it comes to sex. But that’s not the half of it. The deeper scandal of the Church is her set-apartness.

In baptism, every believer is marked as Christ’s own. This is an exodus, a going out from the “facts of life” as the world understands them. And this “going out” irks our present culture, just as it irked the ancient Roman world. The reason is simple: The modern secular or profane world is organized mostly around the natural goods of creation to the exclusion of God.. That means it resents the Church’s supernatural orientation, which seems to be a distraction from what “really matters.” We’ve all heard the complaint that the Church should do more to meet the needs of the poor or of climate change and worry less about liturgies and worship and spiritual realities. Fundamentally, that’s a complaint against holiness as the Church’s highest aim.

And yet, at the same time, the Church’s transcendent orientation fascinates our culture — again, just as it did in ancient times. Holiness offends and in many cases frightens people. As one of the old translations of the New Testament put it, when the angel of the Lord came to them, the shepherds in their fields were “sore afraid.” But at the same time holiness also arrests and romances. We flee from God — people always have — and yet we also crave to come into his presence.

When I was ordained almost 42 years ago, on my ordination card, I had printed these verses from the high-priestly prayer of Jesus in John 17: “As you sent me into the world, I sent them into the world, and for their sake, I consecrate myself so that they too may be consecrated in truth” (John 17:18-19). The key word in those verses is consecrate (Greek: hagiazein; Latin Sanctificare). The sense is to make holy, to set apart and make holy, and the theological context in the 4th Gospel is the sacrifice of the cross and the glory of Jesus. Consecrate, make holy, set apart, the sacrifice of the cross: these concepts, these concepts, these profound mysteries, really spoke to me at the time of my ordination and they still do.

I try to share that whole spirituality of consecration with my own priests whenever the occasion allows. As priests, we’re consecrated to Jesus Christ to serve his people in his Church. That means we invariably embody the scandal and the allure of the divine. Today I want to address that peculiar combination. I think it will help us understand how to respond to the challenges we face today, both as a Church and in our own vocations.

We are consecrated and set apart — this is fundamental to the priesthood. It’s also the root of that interesting combination of offence and allure. Our ordination consecrates us to a life of service. This means performing very tangible tasks like maintaining the parish buildings and, in your context, ensuring that the parish school is well run. But that’s not really the core of our priestly ministry. We serve the People of God — and through them the world — by virtue of the transcendent tasks and responsibilities that are our responsibility.

To put it bluntly: We’re commissioned by God to handle divine things. For example, we’re custodians of the Church’s sacred liturgy and mysteries of faith.. These are rooted in Christ and sanctified by millennia of prayerful study and faithful use. Of course, we’re not the sources of divine grace. Jesus alone is the source. But like the ancient priesthood of Israel, we’re instruments of that grace, which reaches it fulness in the sacraments of the Church that Jesus Christ instituted..

The world’s vision may be impaired by sin, but it’s not blind, which is why our secular culture can’t help but see us as odd and out-of-date, even scary — but nevertheless strangely attractive. Our culture may seem oblivious to God. But even non-believers recognize that our job, as priests, is to stretch the umbilical cord of human nature toward the divine.

This is a perilous thing to do. In Isaiah’s vision, even the angels of God must take up tongs to draw the burning coals from God’s holy altar. This is why priests inspire a kind of fear as well as awe. The fear comes from the fact that our human nature is fallen and fragile – and what if the umbilical cord breaks? The awe comes from recognizing the boldness of the venture. To be God’s instrument and take his most sacred mysteries into our hands, this is an awesome possibility.

We too feel a touch of this fear and awe when celebrating the Mass, and rightly so. The celebration of the Mass is the summit of our priestly vocation. It’s worthy of endless commentary and contemplation. But I want to take a more indirect route to our subject today, one that dwells for a few minutes on what the profane world sees when it sees a priest, which is clerical celibacy.

We know this promise of celibacy is not the essence of our priesthood. It’s a discipline that serves our vocation. It’s not what it means to be a priest. But if you talk to any non-Catholic about the priesthood, I guarantee it will be at the forefront of his or her mind. My house is on the edge of a heavily Moslem neighborhood with a lot of barber shops. You know what barbers are like, They want to talk. They want to know who you are. When I told the barber I was a Catholic priest and bishop, celibacy was the first thing he spoke about, giving me an impromptu disquisition about how unnatural celibacy is for a man. I always find that you are a little at a disadvantage in a barber’s chair, so I kept my answer for another day! Perhaps many Catholics think the same way too.

The world’s focus on celibacy is short sighted, but it reflects a correct spiritual intuition. Celibacy is a powerful sign of being set-apart. In many religious traditions, celibacy marks those consecrated to offer sacrifices, receive revelations, and otherwise enter into commerce with the divine. And, when you think of it, it’s almost obvious that this should be so. Our sexual instinct is so basic to our humanity that its denial marks a break with the ordinary. Our natural religious sense leads us to recognize that God is not nature itself. As a consequence, we cannot enter into the presence of God without in some way leaving the imperatives of nature behind. The enclosing walls of the profane must be punctured in order to gain access to the sacred.

Christians know that grace perfects nature; it doesn’t cancel or destroy nature. This allows us to see that ascetic practices of self-denial such as celibacy are not ends in themselves. If they become our goal, then we’re betraying the Gospel, not serving it. Instead, denying the goods of nature serves the higher end of preparing us for intimacy with God. Jesus calls us to friendship with him, and that friendship draws us beyond nature and toward participation in the divine life.

This sounds reasonable, and it is. Good theology is always reasonable. But that’s not how the world sees celibacy. In the second chapter of Genesis, Adam is alone. God sees that it is not good, and he sets things right. Adam’s union of flesh with Eve both inaugurates and exemplifies the human project in the world. As John Paul II so beautifully explained in his theology of the body, this union of bodies — and thus the human project as a whole — has a spiritual trajectory.

But that said, sexual union remains as a kind of natural sacrament, one that both signifies and effects human connectedness and solidarity. For this reason, clerical celibacy inspires a degree of fear, and even resentment. In a certain sense, priests are traitors. (You can find women who actually say that, and they do so only half humorously.) Celibacy is seen by many as psychologically dangerous. We’re seen as men cut off from the “fullness of life.”

So, yes, the world rejects priestly celibacy. But it’s very important to recognize that celibacy also evokes curiosity and admiration. People sense the spiritual freedom that the promise of celibacy brings. They also impute a kind of spiritual nobility to priestly celibacy, and people want to come into its presence. This is true for non-believers as well as believers. The world is fascinated by celibacy, all the more so in the present age when sex, sexual freedom and sexual identity have become the prism through which so many political, cultural, and moral issues are viewed.

Again, celibacy is not the central truth of the priesthood. As a bishop, I have come to realise that many priests find obedience much more onerous than celibacy. I’m only dwelling on celibacy at the moment only because it’s the fact about the priesthood that the world sees first and foremost. And what the world is seeing is our set-apart vocation. The world grasps the fact that our consecration is for the sake of something supernatural.

This is reinforced by our clerical collars and garb. It’s normal for us in my diocese to dress as priests when we go about our duties. I imagine it is here too. When I come into a room for a meeting with laypeople, I’m always aware that they may be seeing me as something akin to an alien. I’m a man, of course, flesh and blood just like them — but they don’t regard me as one of them. That’s as true for the most ardently secular political or business leaders as it is for the devoted lay leaders in my diocese whom I’m blessed to serve. I can preach again and again about the Church’s spiritual fruitfulness and her commitment to human fulfilment. But laypeople know that I’m outside the great temporal project of human life to be fruitful and multiply.

Over my years in the priesthood, I’ve come to see that this priestly “outside-ness” can be a heavy burden. We’re social animals. We want to be in a home with others. That’s why family is so important. Even with all the tensions and sometimes painful failures in life, our families remain the place where we can just be Joe or John.

The same can be true for school reunions and other occasions when we get together with friends who knew us before we responded to God’s call to the priesthood. I have a friend form my boyhood. . He’s been a very successful man in his professional life. But he told me that he finds it important to go home regularly where people knew him when he was young. “That puts things back into perspective,” he says. It’s his way of returning to the primeval gift of our shared humanity.

This is why I would strongly encourage priests to return to the love of their families and enjoy the companionship of old friends. I am the oldest child of a family of 9 children, 5 girls and 4 boys. Thank God we are all still in this world, at least for the moment. Last year 4 of my siblings and I, 3 sisters and a brother who is also a priest took a trip to my father’s home town in Italy. There were no spouses. It was just us, brothers and sisters. It was delightful. It was so comfortable, so easy. It brought back so many happy memories. I think we laughed for 5 days.

But unlike my successful friend, we need to be honest about who we have become. As priests, we can’t go back and become “merely human” again, because we’re not. My sisters wouldn’t allow it anyway! My friend’s success is very well earned, but it’s not an indelible mark that sets him apart. By contrast, our priesthood is not earned at all. Instead, it’s a vocation given to us by Jesus himself, and ordination marks us in a fundamental way.

It’s a misguided theology of ministry that encourages priests to think of themselves as “just like everybody else.” We’re certainly not better. On the contrary, our sins can be egregious because they’re often spiritualized by our priestly vocations. But we’re different. That’s why our most spiritually mature lay friends love us but treat us as priests.

We are set apart. That’s what it means to be ordained to holy orders. This doesn’t mean standing at a distance. It does not mean clerical aloofness. A priest is consecrated to Christ, and Jesus calls us to build up the People of God. We should always seek to make ourselves available to all who seek God — as well as to those who are lost, doing what we can to guide them toward the Father whom they don’t yet know they desire.

And thank God, in our culture at home, priests have always been pretty close to their people. But being close and being available does not mean being the same. In fact if we’re the same, we are no good to them. As St. Paul observes, though we are one body in Christ, there are many members. Moreover, being available to the world certainly does not make us part of the world. In fact, it’s self-defeating to act as though we are, for what the world needs are visible signs of something greater, something beyond its ken, not something familiar.

Again, we share with all women and men the great gift of human nature, the imago dei. And we share with our brothers and sisters in Christ a common baptism that makes all of us full members of the Body of Christ. I want to stress that there is nothing subjectively “superior” about being a priest. But we are objectively distinct and set apart for a special purpose in God’s economy of salvation. Priests do others no favours by denying the special character of their lives as men ordained into holy orders. In fact, that’s been one of the most damaging problems for the Church in recent decades.

There’s possibly something a little weird about a Dad who wants to be more his son’s friend or pal or classmate than his father. The same holds for spiritual fathers. This doesn’t mean we should avoid strong bonds with lay people, any more than fathers should be remote from their children. But it does mean grasping the fullness of what God has done with us. We have a special role to play in the lives of others (including in the lives of our brother priests). We can bless others in particular and powerful ways when we serve them and love them as priests.

The set-apart character of the priesthood comes to fullest expression in the Mass. Under ordinary circumstances, the priest leads the congregation in the liturgy of the Word. In this role, priests are representatives of the Church’s teaching authority, something they share with bishops and deacons. This does not mean that laypeople can’t speak eloquently and intelligently about scripture and doctrine. In my experience, some can do so far better than many of us. But as members of holy orders, we exercise a sacramental role. For this reason, we need to guard against too much “creativity” in the pulpit. I’m all for lively, effective preaching, but we need always to keep in mind that we’re not just Christians on a faith-journey (though we are that too). As priests, we speak in a unique and formal way for the Church.

In a real sense, our preaching should follow the great Catholic sacramental principle: ex opere operato. That means the subjective conditions of our souls are not decisive for the efficacy of our sacramental ministry. God works through us, often in spite of our infidelities. Sacramental grace depends upon God’s faithfulness to us in Jesus Christ, and his faithfulness, unlike ours, is utterly trustworthy. The homily is not a sacrament, strictly speaking, but it should be understood as a vehicle for God’s grace, which comes in the form of true doctrine vouchsafed by the Church’s unfailing teaching office. We need to proclaim what the Church believes and has always believed.

Even in small group settings and private conversations, a priest should exercise discretion when talking about his interior life. Admissions of personal struggles by the laity can often be helpful in prayer groups and among friends. But the same words spoken by a priest can have the opposite effect. This is another instance when we, as priests, need to reckon with the reality of our ordination. It sets us apart in ways that shape how we are seen and heard. To pretend otherwise misrepresents reality, which then always leads us and others astray.

I’ve deferred until these final minutes the central reality of the priesthood, which is our service at God’s altar. In the old days, altar rails accentuated the distance between the baptized and the inner sanctuaries of God’s most sacred dwelling place. In many churches they’ve been removed, perhaps for good reasons. But it’s very unwise to neglect all signs of the great distance between God and man. We are directed in the General Introduction to the Roman Missal that, whenever possible, the altar should be somewhat elevated and in some way marked as distinct and holy.

Some think that clear indications of the distance between the congregation and the altar of Christ’s sacrifice contribute to clericalism. The opposite is true. The elevation of the altar even a little and the marking of the sanctuary make the priest more aware of his unworthiness. Important questions more naturally arise. By what right do we separate ourselves from the baptized? How can we imagine ourselves worthy to approach the divine? Every step to the altar and into the sanctuary reminds us that we can venture such boldness only on God’s authority, never our own.

Again, it can be tempting to deny reality. These days we want to imagine love means acceptance and affirmation, which involve no movement or change. But God calls the baptized to enter into his household. It’s foolish to imagine that the journey is a short one. Love desires the beloved, yes, and the Word made flesh takes up residence with us. He is nearer than we are to ourselves. We need only open ourselves to his presence and harken to his voice. But he’s with us as the good shepherd to guide us along the narrow path of his cross and resurrection, and that path is not near, familiar, or convenient.

As priests, we share this journey with all the baptized. This is our existential bond. But when we ascend to the altar, we are in the “forefront” of the People of God. We do not leave the laity behind, any more than our ordination leaves behind our baptism. Instead, we venture something frightful, which is to enter God’s inner sanctuary. The great mystery of the Mass comes, of course, from the fact that, as priest, we do more than act on behalf of the baptized. Our ordination conforms us sacramentally to Jesus Christ and consecrates us to the service of the Church. We then act “in persona Christi” who makes us instruments of his saving work on the cross and of his victory over sin and death in his resurrection.

From time immemorial, priestly castes have stretched the umbilical cord of humanity to enter into commerce with God. But only in Jesus Christ do priests recapitulate God’s kenosis, his self-lowering to come into the mortal frame of our creaturely existence. We are often far less than holy as men. But, as priests, we are God’s porters, as it were. We, his unworthy servants, carry his holiness to his people.

As we’ve already seen in these days together, we face many challenges. It often seems that 2017 is a tough time to be a priest. In a certain sense, of course, it is. But I want to close with some words of encouragement. Do not underestimate the power of the priestly vocation. The era of “Father-knows-best” is over. And frankly that’s a good thing, because it normalized clerical life and slotted priests into what became, over time, a very worldly social hierarchy, not a divine one. And while that has faded, faded because it was accretion and not mystery, the reality of your ordination remains.

To be set apart to serve at God’s altar is an extraordinary call. The priesthood remains an offence to the world’s assumptions about what’s real and what matters. As a result, we priests continue to fascinate and inspire. So when we’re assessing things and thinking about our ministries, let’s make no mistake about our present circumstances. In our “whatever” culture, there’s very little that moves, threatens, and inspires people.

It’s striking, therefore, that the secular West continues to vibrate to the priesthood, both in rebellion and affirmation. And that, my brothers, is a very good thing.